The Grenfell Inquiry Phase 2 report published on Wednesday 4 September was the culmination of more than seven years of work by the inquiry and followed publication of the Phase 1 report nearly five years ago.

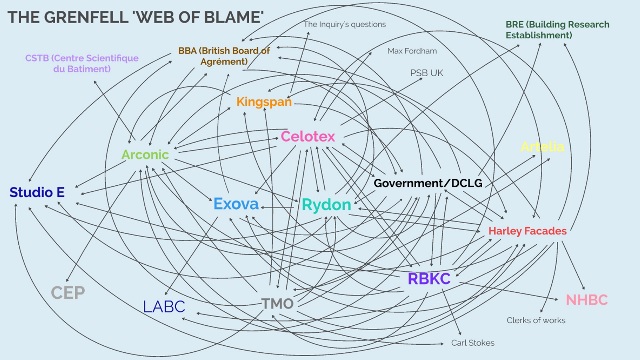

One of the more telling images from the end of the inquiry sessions in 2022 was the Grenfell “web of blame” (see below) reflecting the unedifying spectacle of key players seeking to blame others without accepting responsibility for their own shortcomings. The phase 2 report was a cogent well written report which included assessment by the inquiry of the responsibility and shortcomings of a number of organisations being investigated by the Metropolitan Police and which might now face prosecution.

Lifts and fire control switches

Within the very large report, consideration of the lifts was a relatively small element yet occupying a chapter. The focus was on why the existing lifts were not able to recalled or taken under the control of firefighters. The report was clear that the lifts were not firefighting lifts and was also clear that there was not enough evidence to determine whether it was reasonably practicable to upgrade the lifts as far as physical constraints of the building would allow (the evidence of the expert witness on this was presumably set aside by the inquiry).

While it was preferable that the inquiry did not make recommendations based on insufficiently authoritative evidence, there is an opportunity for useful guidance in this area. (Comment: BS 8899:2016 which was published some after the lift refurbishment and before the Grenfell Tower fire does provide some guidance on the improvement of lifts for the use of firefighters and could be revised.)

The report concluded that the weight of evidence was that the fire control switch had not been regularly tested. The Phase 1 Inquiry Report had already made recommendations about regular inspection and testing of lifts for use for firefighters which resulted in the provisions of the Fire Safety (England) Regulations 2022 (which also require similar checks on evacuation lifts). (Comment: LEIA has published guidance on the lift aspects of the regulations at www.leia.co.uk/technical/leia-newsletter-2/).

A simple action for any company carrying out maintenance or thorough examination of lifts for use by firefighters and evacuation lifts would be to include a check of any switch for fire operation in their schedules and document the results of their checks.

Concerns with switch reliability were compounded by apparent problems with variation in dimensions in drop keys available resulting in some not being able to operate the switch. This resulted in the only lift-specific recommendation: for the government to seek urgent advice from the Building Safety Regulator (BSR) and the National Fire Chiefs Council (NFCC) on the nature and scale of the problem and the appropriate response to it.

There has been some ill-considered criticism of the report’s statement that all modern lifts are fitted with fire control switches (might this inaccuracy have been on the basis of expert witness evidence?). The problem of legacy switches and compatibility with drop keys obtained from a variety of manufacturers is obviously not easily solved but one which the industry and the British Standards Institution could offer assistance to the Government, Building Safety Regulator and NFCC on an appropriate response.

Driving the necessary changes in the construction industry

The Phase 2 Report made a number of very significant recommendations going beyond the requirements of the Building Safety Act and its secondary legislation (applicable to buildings in England). The central recommendation was for a single independent construction regulator to be responsible for a number of functions currently within no less than four government departments (and a number of other functions the report would like to see included such as assessing the conformity of construction products) within a construction regulator which would be a “focal point in driving much-needed change in the culture of the construction industry”.

Comment: the recommendations would be very powerful and entail significant further reorganisation and change following setting up of the Building Safety Regulator which, if the construction regulator would have its remit broadened and deepened with many new responsibilities which would also presumably require resourcing.

Similarly the various departmental responsibilities should be brought together under one Secretary of State who would be able to call on a Chief Construction Advisor for advice. Comment: This is a good recommendation which would go beyond the situation of some years ago when the Secretary of State had access to a Chief Construction Adviser (the recommendation is for a larger role) and the Building Regulations Advisory Committee (BRAC) since disbanded with the new BSR and its Building Advisory Committee (BAC).

Given the importance to the new building safety regime of the definition of a higher-risk building, the report noted that the height/storey-based definition is essentially arbitrary and recommended that the definition is reviewed urgently noting for an HRB: “More relevant is the nature of its use and, in particular, the likely presence of vulnerable people, for whom evacuation in the event of a fire or other emergency would be likely to present difficulty”.

The implication from this statement might be that some buildings below the 18 m/ 7 storey thresholds might be considered as HRBs on the basis of numbers of occupants who might require level access (“vulnerable people” as described in the report) and the length/difficulty of any evacuation.

Functional requirements in the Building Regulations and statutory guidance in Approved Documents (in particular AD B)

Note: the legislation referenced here is applicable to buildings in England.

While the Phase 2 Report did not suggest that expressing the legal requirements of the Building Regulations as functional requirements was in itself unsatisfactory, it was very concerned about how the functional requirements have been supported by the guidance in Approved Documents. There were recommendations for:

> The statutory guidance generally, and Approved Document B in particular, to be reviewed and revised as soon as possible.

> The statutory guidance to contain a clear warning in each section that the legal requirements are contained in the Building Regulations and that compliance with the guidance will not necessarily result in compliance with them. (The report observed that levels of competence in the construction industry are generally low and that many incorrectly treated the statutory guidance as containing a definitive statement of the legal requirements.)

> The assumption in Approved Document B about effective compartmentation on which a stay put strategy rests should be reconsidered. The report recognised that new materials and methods of construction and the practice of over-cladding existing buildings make the existence of effective compartmentation a questionable assumption. (It might also be observed that occupants voluntarily evacuating a building when aware of a fire might also point towards stay put no longer being a tenable or valid approach in many situations.)

> Guidance should draw attention to the need for a calculation of the likely rate of fire spread and the time required for evacuation, including the evacuation of those with physical or mental impairments (note the recurring concern with this group) by a qualified fire engineer.

> Membership of bodies advising on changes to the statutory guidance should include representatives of the academic community as well as those with practical experience of the industry (including fire engineers) chosen for their experience and skill and should extend beyond those who have served on similar bodies in the past.

The Phase 2 Report did note that greater competence is required in users of performance-based building requirements (such as Approved Documents) compared with following more prescriptive requirements.

Comment: This would be a good moment not only to review the process for producing statutory guidance (and who advises on the content) but also the relationship between the Building Regulations and the statutory guidance and standards on fire safety developed by the British Standards Institution (BSI) which has a model for involving a broad spread of stakeholders.

Comment: It is hoped that in responding to the recommendations in the Phase 2 Report, the subject of second stairs (and means of escape generally) in residential buildings with top floor greater than 18 m height can be revisited providing greater clarity for what will be required to meet the functional requirement in the Building Regulations and also more fully addressing the Phase 2 Report recommendations for the evacuation of those not readily able to use stairs.

The evacuation of those with physical or mental impairments

The Phase 2 Report rightly concluded by looking at the needs of vulnerable people. There were several references to the needs of vulnerable people including their evacuation – some of these were touched-on in the earlier discussion on Building Regulations and statutory guidance in Approved Documents.

The Phase 1 Report had included a recommendation that the owner and manager of every high-rise residential building be required by law to prepare personal emergency evacuation plans (PEEPs) for all residents whose ability to self-evacuate may be compromised (such as persons with reduced mobility or cognition). In the intervening period, many have felt that this recommendation had not been adequately addressed by the DLUHC (now MHCLG) so it was no surprise that the Phase 2 Report, in relation to vulnerable people, recommended that further consideration be given to the recommendations in the Phase 1 Report.

It was good to see a Written Ministerial Statement from MHCLG on 2 September that The Home Office will bring forward proposals in the Autumn to improve the fire safety and evacuation of disabled/vulnerable residents in high-rise and higher-risk residential buildings in England in response to the Grenfell Tower Inquiry’s Phase 1 recommendations that relate to Personal Emergency Evacuation Plans, or PEEPs.

While the Home Office is not responsible for the Building Regulations (which is under the MHCLG) and Approved Documents (prepared by technical teams in the BSR), if the recommendations to look again at these are taken up then there will be a fresh opportunity to rethink the requirements for new buildings.

Beyond the Building Regulations and statutory guidance which are the benchmarks for new buildings, still more guidance is needed to assist with the improvement of building safety of existing buildings where the physical constraints of the building provide challenges compared to new-build.

Other recommendations

The Phase 2 report included 58 recommendations which would, if adopted, have very significant impacts on the construction industry and its regulation, including some very significant implications for our sector. Some of these (this article is in no way intended to be a summary or overview of the Phase 2 report and these titles and content are offered from a personal perspective) included the following.

> the establishment of a body of professional fire engineers, properly regulated and with protected status and the introduction of mandatory fire safety strategies for higher-risk buildings

(Comment: The term “engineer” is not protected in the UK – and so if fire engineers were to have protected status then presumably many other professional engineering institutions involved in building safety such as structural engineers and many others would also like their professions to have protected status);

> the regulation and mandatory accreditation of fire risk assessors;

> the establishment of a College of Fire and Rescue to provide practical, educational and managerial training to fire and rescue services; and

> the introduction of a requirement for the government to maintain a publicly accessible record of recommendations made by select committees, coroners and public inquiries, describing the steps taken in response or its reasons for declining to implement them.

> a licensing scheme operated by the construction regulator for principal contractors wishing to undertake the construction or refurbishment of higher-risk buildings. (It is unclear whether the Inquiry believe that the new responsibilities for principal contractors do not go far enough but such a measure would have obvious implications for smaller contractors such as lift contractors carrying out lift refurbishment work on HRBs.)

Conclusion

The Phase 2 Report very cogently identified the many factors which came together resulting in such a large loss of life in the Grenfell Tower fire. There is no quick fix as there were multiple failings which showed a poor culture for building safety. The Government has already put in place a new building safety regime (in England) which it is hoped will improve the culture of the construction industry. The Phase 2 Report identified a number of further recommendations which will need to be carefully considered by Government which will need to decide how it wishes to respond.

In the Prime Minister’s statement to the on 4 September, he stated that the government will respond in full to the Inquiry’s recommendations within six months. While this is further delay, many of the recommendations have far-reaching implications which will take time to consider. Sustained effort across the industry will then be needed to bring the changes required.

The most harrowing section of the Phase 2 Report was the chapter on the deceased which recalled each of the people who died as a result of the fire. One of the most powerful theatrical experiences the author has experienced was at the 2023 National Theatre production of “Grenfell – in the words of survivors” where towards the end of the play, 72 of the audience were asked to vacate their seats to sit in the central area of the floor to represent those that lost their lives as a result of the fire – being one of the 72 was a difficult, emotional and though-provoking experience.